18 Jan Myles Bautista Interview

From A to Z and back again.

By Aaron Bonk

Photography courtesy of Myles Bautista

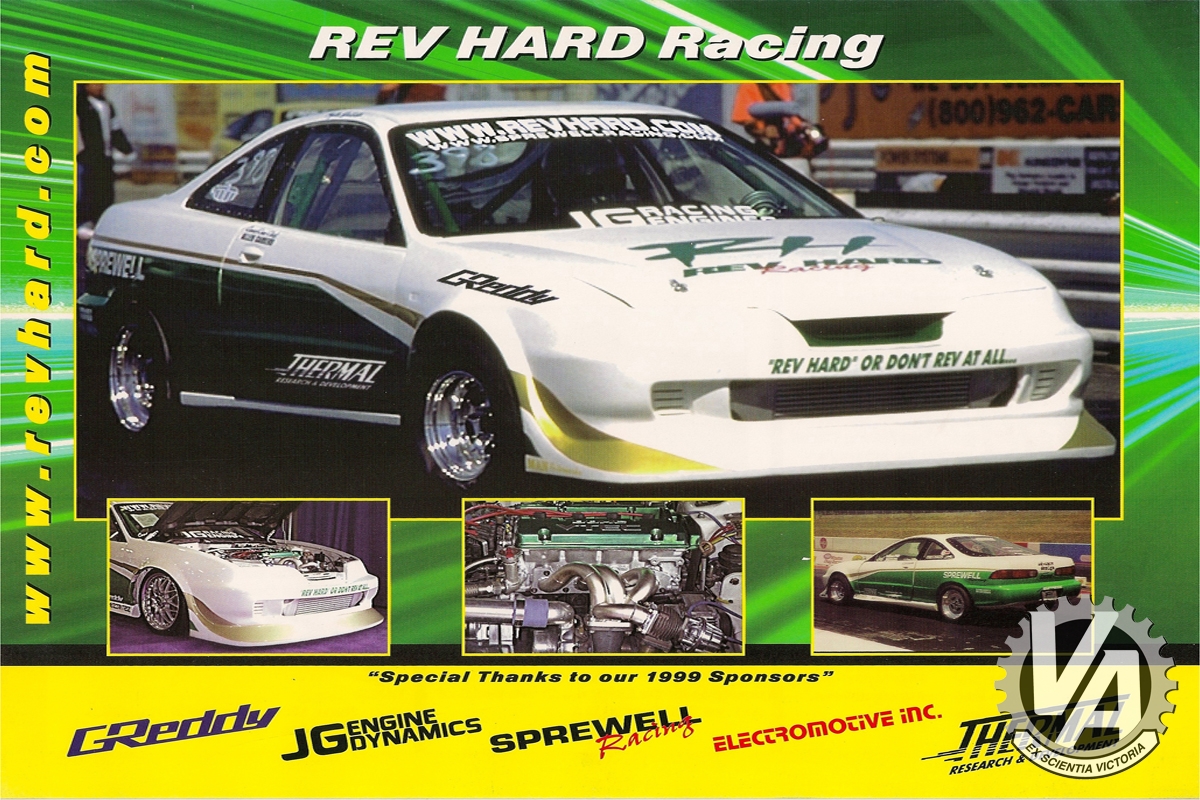

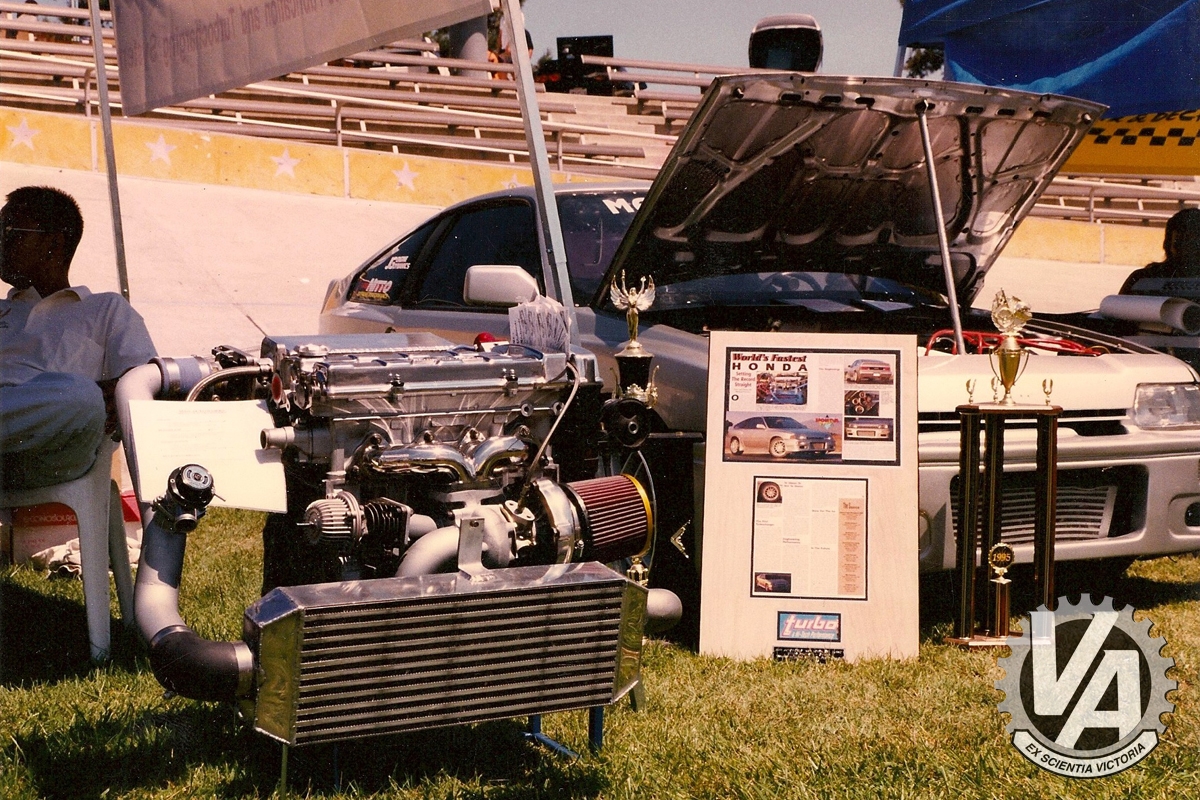

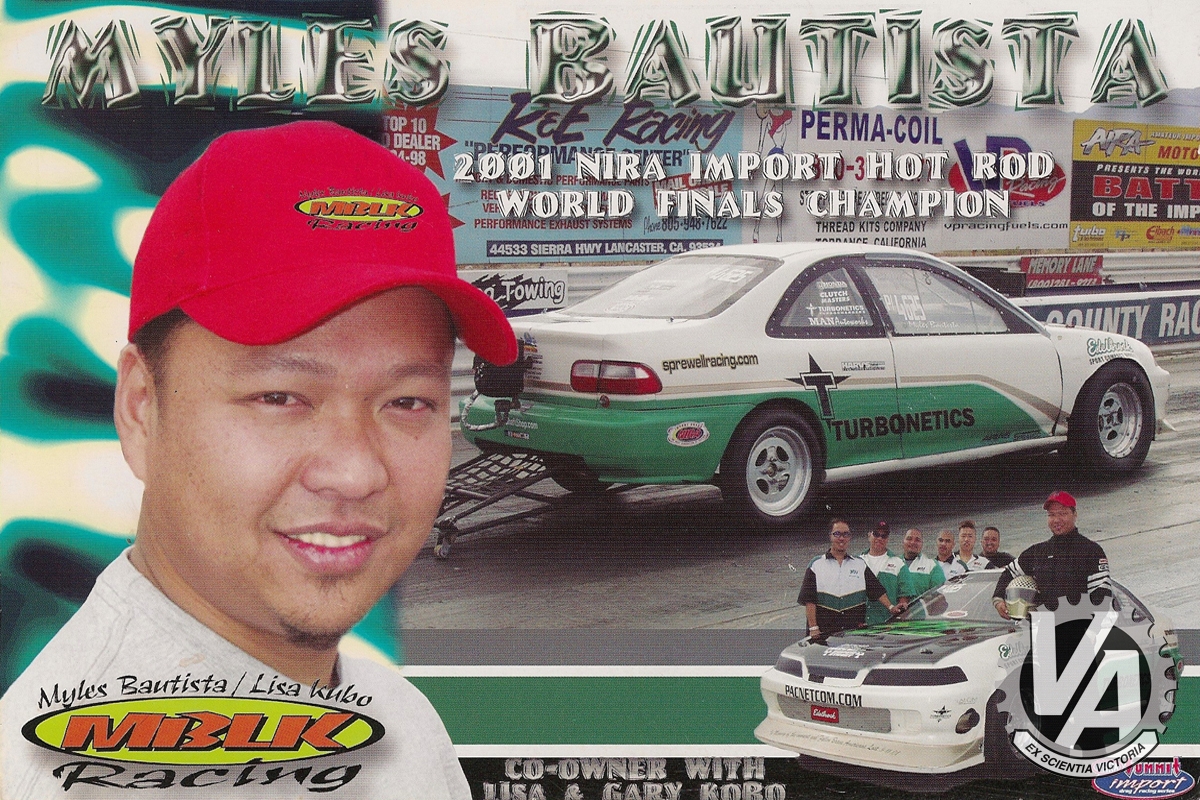

As far as the early 1990s are concerned, Hondas and turbocharging will remain strange bedfellows. With the exception of the HKS turbo kit designed for 1.6L, twin-cam D-series engines, Honda powerplants remained, by and large, of the naturally aspirated persuasion. Myles Bautista changed all of that. His efforts at legendary Honda tuning facility JG Engine Dynamics, later Turbonetics, and at his own organization, Rev Hard, helped usher in the era of the turbocharged Honda. Considered by many as the father of Honda forced induction, Bautista is credited for executing the first 12-second quarter-mile pass and for developing among the first Honda-specific tubular exhaust manifolds. Perhaps ahead of his time, Bautista experimented with large-frame turbos and went on to co-found Rev Hard, a pioneering organization that specialized in Honda turbocharger systems. Bautista undoubtedly revolutionized Honda performance, set records, founded a million-dollar company, and, not unlike other legends, left on an unannounced, undetermined hiatus in 2005. But Bautista has since returned. The following recounts where he came from and where he’s headed.

VA: What’s your earliest Honda-related memory?

MB: When my dad gave me an ’85 CRX HF as a graduation present from high school during my senior year. That was the beginning of me trying to learn, bolting on a bunch of parts, trying to see how I could make an HF go fast. That was 1989.

VA: Did you even care about Hondas or was the CRX your dad’s choice?

MB: No, I didn’t even care about Hondas. I had a Toyota pickup truck that I drove in high school. That was the scene in the ’80s. As far as street racing went, all my cousins drove Corollas and Celicas. The first thing they said was, “That can’t compete. Nobody drag races a FWD car!”

VA: Explain the events that led to you creating Rev Hard.

MB: After I spent a ton of money on the CRX, I would still get beat at the street races. I went carbureted, nitrous, new cams every weekend, every type of electronic ignition. I needed a change. I’d been looking at a lot of Carboy magazines, and that’s when I noticed that the [Japanese] CRX came with a different motor—a twin-cam, 1.6L—what they called a ZC. I got a hold of one of those motors, put it in, got quicker, but still wasn’t quick enough. That was 1990 or 1991.

VA: What’d you do next?

MB: I bought a universal turbo kit from HKS. I didn’t know where to hook up the water lines so I took it to a turbo shop, AK Miller in Rosemead [Calif.]. They were the turbo gurus back then. I picked up the car with a $2,800 bill, looked at it and said, “What happened to the HKS turbo?” They said, “You don’t want that on your car; it’s too big. You need one of these T25 Garrets.” I just figured the T3 turbo that HKS provided was too big for my motor. I got back to my dad’s shop, looked at the turbo kit, and saw that they didn’t even hook up the water lines! The only reason I paid the $2,800 was because I wanted everything done right and I wanted to know how the water lines hooked up. I called them up and they said that I didn’t need them. I was like, why would a turbocharger have such a thing and not need it? That was the first step toward me building Rev Hard.

VA: An important step that you probably didn’t even realize at the time. What else did you do to make that ZC engine more powerful?

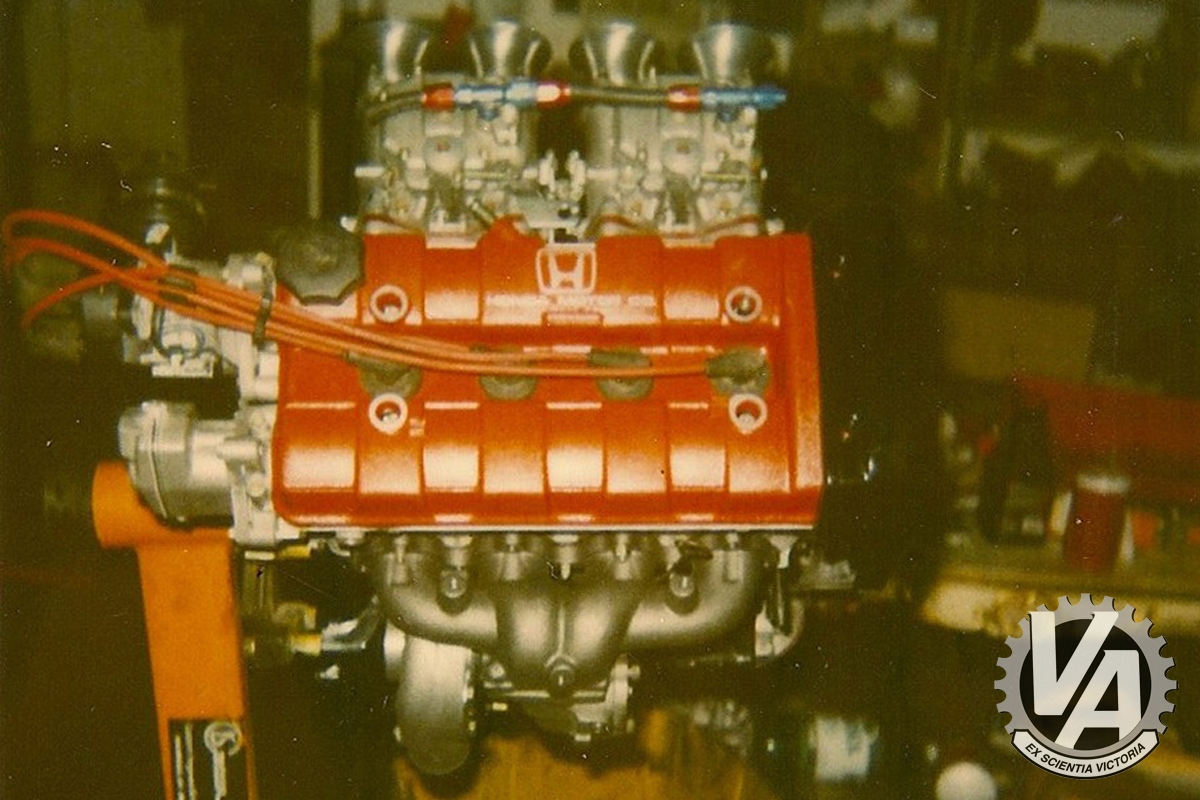

MB: I ran twin side Mikunis on it. I dealt with JG Engine Dynamics and we put high-compression [Arias] pistons in it, nitrous, all that stuff. Nobody made cams back then, but I had a good friend who worked at ISKY [Racing Cams]. All those times they were grinding cams, they never knew that a Honda turned counter-clockwise, so they were grinding the cams backward. The cams were working, but the profiles were completely off because it was a counter-clockwise motor [laughs].

VA: But they worked?

MB: Yeah, they still made more power. There was a lot of trial and error back then. We didn’t have the privilege of having the internet so everything we did was our own innovation.

VA: What did you do for fuel management?

MB: I had a blow-through, twin-Mikuni, carbureted turbo setup, which actually helped at the street races. Since I didn’t have the transition from the primary jets to the main jets, the car would bog, which would help me gain traction. So while my car was sputtering, it was actually gaining traction. By the time it cleared up, the car would move [laughs].

VA: Prehistoric traction control, no?

MB: Yep [laughs].

VA: Did you have any experience with turbochargers prior to the HKS kit?

MB: None. That kit started everything, and that bad experience with AK Miller, well, I actually have to thank them for that. We’ve learned that Honda motors are a different kind of animal when it comes to their efficiency. Even when I worked for Turbonetics R&D, the old school guys, they were really black-and-white: “The efficiency of the turbocharger, the maps. This is the exact turbo that you need for that particular sized motor.” I don’t have a mechanical engineering degree, but one thing that I love to do is experiment. Why don’t we put this on and if it works, it works. If it doesn’t, then we keep going. I think that if it wasn’t for me, people would still be running T3/T4 combinations.

VA: What finally led to you forming Rev Hard?

MB: Later on I went to DRAG to buy a tubular [exhaust] manifold. DRAG was one of the first companies to make turbo kits for Hondas. I ordered it, went to go pick it up, and $450 later got a tubular log manifold. I brought it back to my dad’s shop and he was like, “You paid $450 for a log manifold? We can do a lot better than this.” I put the manifold on anyways, made good power out of it, but from the looks of it, I was really unhappy. So I decided to use my savings, bought a TIG welder, and made my first tubular manifold. It made like 20 hp and 30 lb-ft. I thought, we’re onto something here. I started making those manifolds for my car club, Team Precision. I did all of their custom turbo kits. After that I thought, why don’t we start a company? So Ramon Rayos, who’s in the Philippines now running his drifting events, Allen Camero, and I started Rev Hard. We didn’t know it would turn into a million-dollar company.

VA: Where you surprised when you blew your first turbocharged engine?

MB: Yes, but when we blew it, we tried to figure out a way to make it stronger. When I worked for JG, that’s when Javier [Gutierrez] and I came up with the idea to weld the block shut. We had those aluminum girdles made and started welding them in. Those held for a while; we made 470 hp. Then we found LA Sleeves and JG started sleeving blocks. That’s when we broke the 600hp mark.

VA: You worked at JG Engine Dynamics first, right?

MB: Yeah, that was when JG started with Hondas. When I first went to JG, I told him all of my problems: the turbochargers, the blocks, all that stuff. He was like, “Oh, yeah, we’ve done all those things on cars before.” To this day, I’ve still never seen any of those cars that JG supposedly did before the first time I walked into that shop. But when we hit the record of 12.21-seconds—the world’s fastest time and first 11-second setup—his phones started ringing off the hook.

VA: What happened after JG, when you were turbocharging your friends’ cars? How’d that transition to Rev Hard?

MB: Once I started doing those one-off kits for the clubs, these guys would go street racing, they’d beat somebody, and after that I’d have somebody else calling me, telling me they wanted whatever setup they’d lost to: “I lost to a green Civic at the Gardena street races; I want the same setup he has!” So I started doing custom turbo kits for other people. Once the car [CRX] made it into the magazine, it [Rev Hard] became a business. That’s when we came out with the cast manifold and Rev Hard took off from there.

VA: You worked for Turbonetics while you ran Rev Hard. What was your role there?

MB: I was lead tech support and company happy hour leader [laughs]. I just basically dug up all of these old turbine wheels, compressor housings, and compressor wheels and had the guys downstairs assemble turbos for me to try out on the weekend and come back with results.

VA: Did you help mainstream the T3/T4 hybrid turbocharger?

MB: Yeah, I just kept on going bigger and bigger and bigger. That’s one thing that I’m grateful for with working for Turbonetics. They gave me the whole R&D department to just make different turbo combinations. If you noticed, those years from 1999 to 2001 were dominated by Turbonetics—from Lisa Kubo to Chris Rado to Kenny Tran. Turbo companies like Garret and Borg Warner weren’t participating in this sport until GM got involved. I think if it wasn’t for Turbonetics, they wouldn’t be here now. Another up-and-coming turbo company tried offering me money to give them Turbonetics and Spearco product sources, but I didn’t. I was too loyal.

VA: Rev Hard was founded shortly after DRAG, right?

MB: Yeah, and after I invented the cast, tubular manifold, which I then mass-produced, I started selling them to DRAG and Turbonetics.

VA: DRAG seemed like more of a household name but Rev Hard was the race-oriented option. Were the two fierce competitors?

MB: I didn’t realize that we were that neck-and-neck with each other until I worked for Turbonetics and saw the numbers—three…four-hundred-thousand a year in turbochargers. That was how many turbos DRAG was buying. That was kind of like a conflict of interest but, you know [laughs]. I didn’t really care about those numbers, though, because I supplied DRAG all of their manifolds.

VA: DRAG later made its own manifolds, right?

MB: Yeah, those later ones were outsourced to Columbia. I know because that same Columbian guy walked into Turbonetics and tried selling some of those.

VA: With Rev Hard vs. DRAG, the consumer really couldn’t go wrong. Can a company like Rev Hard compete today with so many inexpensive, overseas-made alternatives?

MB: Once you go overseas, you lose control of everything. When I started, some guy hit me up and was like, “Hey, we can make this [tubular exhaust manifold] in Thailand for cheaper.” Sure enough, when we got the order in, Turbo magazine came out and that same exact manifold that we sent to Thailand was already on a new products press release for another company.

VA: So the manufacturer who was mass-producing them for you sold your design to another company?

MB: Exactly. Sending stuff overseas, there’s no loyalty. You open yourself up to copycats. You can’t trust those guys.

VA: Does that hurt the entire industry or just companies like Rev Hard?

MB: It put a hurt on Rev Hard and our industry. Now there’s one less company out there innovating. I left the company in 2005, when all the eBay kits started coming out. That’s what put a hurt on manufacturers like Rev Hard.

VA: Why did Rev Hard ultimately close down?

MB: Well, Ramon ended up going home to the Philippines and Allen didn’t know how to handle the business aspect, like the paperwork and marketing. The team wasn’t whole after that. I took some of my share and tried to go into real estate. What a failure that was! Everyone knows what happened to the market in 2007.

VA: Ouch. Where did Team Precision rank among the 1990s street racing mix?

MB: We started Team Precision in high school, when I got the CRX. I built the club 50 cars deep. The majority of the guys from that crew are a big part of our industry now. I mean, you’ve got Rob Choo’s [former Turbo magazine and DSPORT editor-in-chief] brother Nee, who owns a dismantling yard; he was one of the first guys that we did the 1.8L LS changeover for in an ’89 Civic. Rob was a young kid that used to go with us to the street races. Mike Chung, marketing director for GReddy, I turbocharged and blew up his cars many times. Kenji Sumino [general manager of GReddy] had an ’89 Civic DX that we put a ZC motor in and turbocharged. Mike’s ’90 Civic, man, talk about testing stuff out. I had Mike’s car twin-side carbureted when I did all of the development for Mikuni and AEM back in 1991.

VA: How do you feel about street racing?

MB: It was fun until my best friend who made Team Precision with me got shot. When all the gangbangers started going, that’s when I quit, which was in 1993. He got shot and street racing was not worth it anymore. That’s when we started thanking Frank Choi for doing the Battle of the Imports.

VA: How important was the Battle of the Imports to this industry?

MB: It was very important. The challenges of making a front-wheel drive car go fast—you couldn’t really tell [how fast it was] through street racing. That’s when companies like JG and AEM got involved. I don’t think AEM or other companies would be here today if it weren’t for Battle of the Imports.

VA: Talk about that record-setting 12.21-second pass?

MB: That was 1994 when I went 12.21 on a 20-inch slick. People said, “Oh, it’s corrected.” You can correct it all you want. Nobody ever runs 20-inch slicks and goes 12.21 at 118 mph.

VA: Was that with the ZC engine?

MB: Yeah, the ZC. After I broke that record, I got a call from a guy from Bahrain. He goes, “Are you selling that motor setup.” I said, “Yeah, $9,500…engine, tranny, TEC-II, everything.” He calls back the next day and goes, “Hey, did you get my check for $10,000?” I was like, oh, damn! I took everything out and switched to the B16 setup.

VA: Electromotive’s TEC-II played an important role in early Honda tuning, didn’t it?

MB: [laughs] TEC-II was one of the first companies to get involved in our industry. Before there was Accel [DFI] there was TEC-II. AEM sold a lot of TEC-IIs back then. I worked with John Concialdi of AEM. Whatever he said, I’d do to my car. I’d rather have an 8 x 8 table than a 12:1 rising-rate regulator. The biggest drawback with the TEC-II was the crank trigger wheel. I’d downshift on the freeway, the car would shut off, and all of a sudden I’d see this magnetic wheel rolling next to me [laughs].

VA: Tell us about your Integra that you later raced.

MB: I stepped up to an H-series with that car. With the B-series we were making 500 hp, but the H made 600 hp much easier. The problem with the H was that we had to use custom axles. The car was a hit or miss. It would either go low 10s or break an axle. I met Frank [Rehak] from the Driveshaft Shop at my first race on the East Coast in New Jersey. Actually, I don’t think he called himself “Driveshaft Shop” yet, but he started making me axles. He always sent me axles to try out because he knew I was the one who’d break the most. I got sick of the H, though, and put the B-series in because of its bolt-on axles. The B-series actually ran 9.50s. That’s when it ran consistent.

VA: You guys were one of the first to run 26-inch slicks, weren’t you?

MB: Yeah, and every time I came out with something new on my cars, like the 22-inch slicks, the 24s, and then the 26s, people would laugh at me. Oh, how I wish I met Frank back then. My CRX killed everyone power-wise but couldn’t run because of axles.

VA: What are some other innovations from that period?

MB: We needed more downforce for the CRX so my dad, who owned a body shop and was into body kits, helped out. We started making these aluminum canards to add downforce. After that, all these carbon-fiber canards started popping up. That was sometime around 1993 or so.

VA: How quick did the CRX ultimately go?

MB: The CRX went 10.40s, which was controversial because I was doing 1.4- and 1.5-second 60-foots. They [competitors] were saying, “Oh, that’s not real. There’s no FWD car that’s going to do 1.5-second 60-foots.” Everybody said it was impossible, but what are cars doing now? 1.1s and 1.2s [laughs].

VA: How’d you do it?

MB: The TEC-II had a feature on the clutch that acted as a two-step. The two-step back then wasn’t really a fast-cut rev-limiter, so I was activating the TEC-II, keeping it on a timer when it would launch on the rev limiter. No FWD car had done that yet.

VA: Name some other notable racers of that era.

MB: The big names from the street races who I’d give credit to are Archie Madrazo, Tony Fuchs, and Junior Asprer. The funny thing is, we were all rivals at the street races. These guys would’ve probably boxed if they needed to. Thank God for Frank Choi and the Battle of the Imports. You couldn’t fight at the Battle of the Imports. Although, I almost did with Jeremy Lookofsky one time and then Ron Bergenholtz.

VA: What happened?

MB: Well, with Jeremy, there was an incident that was between me and Tony Fuchs and Jeremy wanted to get involved. They were teammates. With Ron, I’d made a pass in the CRX and beat his brother [Ed]. He started calling me a cheat because of my tow hook. But we’re all old friends now [laughs].

VA: Tell us more about the infamous tow hook incident.

MB: Yeah, the tow hook incident where it tripped the lights. I was like, “Alright, call me a cheat, we’ll take off the tow hook and go from there.” I gotta admit, the only reason I made that was so that I could cross the finish line first. Who would have thought that all these companies would be making tow hooks and be selling millions of them. That’s now JDM [laughs].

VA: Did you know what the competition had in store before you’d arrive at the track?

MB: No, we never knew. One regret I have is when my chassis guy told me, “Hey, if you’re not getting any traction, put a wheelie bar on.” I told him that I wasn’t gonna look stupid putting a wheelie bar on a FWD car. Later, Ron and Ed Bergenholtz were creating all this hype, saying they had something for us at the next event. Sure enough, when we pulled up to Battle of the Imports we saw Ed Bergenholtz’s car on a flatbed with a wheelie bar. Ever since that day it was like, whatever I can think of, I’d just do it. If it worked, it worked. If it didn’t, it didn’t.

VA: How much money were you spending each year campaigning your cars?

MB: We were spending a lot of money on the CRX. I probably had six credit cards maxed out at $5,000 a piece. When we got to the point where we were racing [the Integra] in NHRA, we were spending $150,000, $200,000 a year, and we couldn’t even compete with GM. That’s what made us quit. We’d go to a track, and if we broke a transmission, in 45 minutes we’d be lucky to have a new one in. But there we were, watching GM and Mopar every round change their motors and transmissions. I stopped because I just couldn’t compete with them.

VA: You helped turbocharge many of the quickest Hondas from that period, didn’t you?

MB: When I was at JG, I was the one who sold the turbochargers for everyone’s cars. From Steph [Papadakis] to Tony Fuchs—even though DRAG, for some reason, found a way to put their name on his car. All of the cars that came out of JG pretty much had my turbo combination. And lets just say that the guy who I developed that turbo with was offered big bucks from David Shih for it. Then, what do you know, the whole Wicked crew had that turbo.

VA: You regularly helped your competition.Were you all pretty close friends?

MB: To me, whoever came knocking on my door for help, I’d always try to help. It wasn’t even about the money. Back then, KG [Precision Engineering], JG, and a couple of other guys were all engine builders but they weren’t turbo specialists. If you look at that era, I would say that in the Quick Eight category, six were from Rev Hard. That’s what I was proud of, building Rev Hard. They weren’t just competitors because they ran the name and supported the company. But when corporate got involved, those people got to decide whose names were on the cars. That’s when I got kind of heartbroken. As soon as it went corporate, they started forgetting how they got to where they were and the [Rev Hard] stickers came off. During that time, there was also an up-and-coming turbo kit company that had a good marketing strategy. Instead of helping the no-name guys, they found the guys who were already fast and had them run their product. It was a company in Arizona that, I must admit, had nice robotic welders. To me, I don’t give a Frak about them. I’m more bitter about the no-name racers that [Rev Hard] made famous who had no loyalty.

VA: Did you ever think Honda performance would’ve grown as much as it has?

MB: No, I never thought that it would have kept on going. After losing everything and getting back into the car stuff, that’s when I thought, man, why did I leave because I could’ve kept on developing something new, especially with the K-series stuff. Today I work with a lot of Subies and EVOs but I’m pro-Honda all the way, no matter what I do. Right now, the Subarus and the EVOs are the ones paying the bills. The Honda guys are not paying my bills [laughs].

VA: What do you think about present-day Honda Motor Co.?

MB: The newer cars going electric, that’s another challenge. If you can make 500 hp on an electric car, then so be it. One great thing about Honda is its technology. They don’t spend all of that money on racing to not come out with the best engineered motor. It’s sad because if Honda paid attention to our sport and supported us against GM, I think the sport would’ve reached another level. Instead, GM killed all of us and the sport died. I’ll still die Honda, though. I’ve got an old Toyota that’s getting a Honda [S2000] engine put in it. After I got married with kids, I had to have a fast four-door, which is why I got into EVOs, but when I get back on the strip it will be in a Honda. Honda for life!

VA: If you could have any Honda, what would it be?

MB: I really want to get my hands on a CR-Z with a K-powered engine. Of course, I’d take all of the electric stuff out of it. I like the CR-Z body style. It’s a rebirth of the CRX. Honda should send me one for being one of the OGs that tried to make a CRX HF fast [laughs].

VA: What are you up to nowadays?

MB: Makspeed is my new company, my dyno shop in Temecula [Calif.]. I’m trying to learn new stuff again and come up with something new. I’m also working with Xionics Performance from Mexico, who actually wants to help bring Rev Hard back. I would rather have parts made by our neighbors than across the Pacific [laughs]. I’m also working with the younger generation that’s passionate about cars and Hondas. I’ll make one of them famous and maybe they’ll stay loyal.

VA: Any closing words?

MB: Hopefully we can bring out some of the old school guys and have a reunion race. We probably can’t keep up with the new guys, though. They’re unreal. The technology that they have is just remarkable. I would’ve never thought. I think we could’ve gotten to where these guys are at now, but I think with corporations like GM and Saturn stepping in, it just killed the sport. If Honda would’ve given us backing to compete against them, it would’ve been a different story.

No Comments